Stages of community building

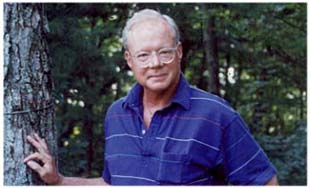

Scott Peck was an American psychologist, famous for his ten million copy selling book The Road Less Traveled. Scott developed a four stage classification of community building that’s proven popular over the years. Scott himself never claimed that all communities go through these stages or that communities happen by formula, only that this was the usual order of things.

Scott Peck was an American psychologist, famous for his ten million copy selling book The Road Less Traveled. Scott developed a four stage classification of community building that’s proven popular over the years. Scott himself never claimed that all communities go through these stages or that communities happen by formula, only that this was the usual order of things.

Pseudocommunity

For many groups or organizations the most common initial stage, pseudocommunity, is the only one. It is a stage of pretense. The group pretends it already is a community, that the participants have only superficial individual differences and no cause for conflict. The primary means it uses to maintain this pretense is through a set of unspoken common norms we call manners: you should try your best not to say anything that might antagonize or upset anyone else; if someone else says something that offends you or evokes a painful feeling or memory, you should pretend it hasn’t bothered you in the least; and if disagreement or other unpleasantness emerges, you should immediately change the subject. These are rules that any good hostess knows. They may create a smoothly functioning dinner party but nothing more significant. The communication in a pseudocommunity is filled with generalizations. It is polite, inauthentic, boring, sterile, and unproductive.

Chaos

Over time profound individual differences may gradually emerge so that the group enters the stage of chaos and not infrequently self-destructs. The theme of pseudocommunity is the covering up of individual differences; the predominant theme of the stage of chaos is the attempt to obliterate such differences. This is done as the group members try to convert, heal, or fix each other or else argue for simplistic organizational norms. It is an irritable and irritating, thoughtless, rapid-fire, and often noisy win/lose type of process that gets nowhere.

Emptiness

If the group can hang in together through this unpleasantness without self-destructing or retreating into pseudocommunity, then it begins to enter “emptiness.” This is a stage of hard, hard work, a time when the members work to empty themselves of everything that stands between them and community. And that is a lot. Many of the things that must be relinquished or sacrificed with integrity are virtual human universals: prejudices, snap judgments, fixed expectations, the desire to convert, heal, or fix, the urge to win, the fear of looking like a fool, the need to control. Other things may be exquisitely personal: hidden griefs, hatreds, or terrors that must be confessed, made public, before the individual can be fully “present” to the group. It is a time of risk and courage, and while it often feels relieving, it also often feels like dying.

The transition from chaos to emptiness is seldom dramatic and often agonizingly prolonged. One or two group members may risk baring their souls, only to have another, who cannot bear the pain, suddenly switch the subject to something inane. The group as a whole has still not become empty enough to truly listen. It bounces back into temporary chaos. Eventually, however, it becomes sufficiently empty for a kind of miracle to occur.

Community

At this point a member will speak of something particularly poignant and authentic. Instead of retreating from it, the group now sits in silence, absorbing it. Then a second member will quietly say something equally authentic. She may not even respond to the first member, but one does not get the feeling he has been ignored; rather, it feels as if the second member has gone up and laid herself on the altar alongside the first. The silence returns, and out of it, a third member will speak with eloquent appropriateness. Community has been born.

The shift into community is often quite sudden and dramatic. The change is palpable. A spirit of peace pervades the room. There is “more silence, yet more of worth gets said. It is like music. The people work together with an exquisite sense of timing, as if they were a finely tuned orchestra under the direction of an invisible celestial conductor. Many actually sense the presence of God in the room. If the group is a public workshop of previous strangers who soon must part, then there is little for it to do beyond enjoying the gift. If it is an organization, however, now that it is a community it is ready to go to work-making decisions, planning, negotiating, and so on-often with phenomenal efficiency and effectiveness.”

Excerpt from the book A World Waiting to be Born by Scott Peck (Bantam Books, New York, 1993)

Scott was also a spiritual guy as you can tell. The stages may seem a bit too intense or philosophical when applied to a lot of communities. But I remember reading about these stages years ago, and the more time that passes the more I think there’s something to them. When a community first begins to form, it isn’t really much of a community at all. Everyone is new to everyone else and naturally trying to make a good impression. People generally don’t criticize and try to be nice. The problem with everyone “being nice” is that it can lack authenticity.

I remember going out to a Hamilton tech startup event a couple years ago where entrepreneurs were presenting their products. Nobody in attendance criticized anything, despite some pretty glaring problems. Maybe people just didn’t feel comfortable criticizing, sometimes it’s not so much a matter of being too nice as it is not feeling qualified or knowledgeable enough to deliver criticism.

I remember going out to a Hamilton tech startup event a couple years ago where entrepreneurs were presenting their products. Nobody in attendance criticized anything, despite some pretty glaring problems. Maybe people just didn’t feel comfortable criticizing, sometimes it’s not so much a matter of being too nice as it is not feeling qualified or knowledgeable enough to deliver criticism.

That’s part of why peer-to-peer relationships, especially founder-to-founder relationships, are valued the way they are. It can be aggravating to receive criticism that’s from a position of unjustified authority or knowledge. Nobody is a level 10 black belt guru expert engineer social master spirit guide. People want to talk to their peers first and foremost, because those are the people that really understand the challenges involved. It’s why the best mentor relationships become peer to peer relationships overtime too.

At a more recent Hamilton tech startup event somebody very openly questioned a fundamental aspect of a startup’s business model. They went beyond asking the “generic business model question” and critiqued a specific aspect of the business model as being fundamentally unworkable. I think some people thought he was heckling. But the criticism was more constructive than abrasive. It was authentic communication, delivered as one peer to another, openly and honestly. Who knows whether his criticism was correct or not. But either way, the entrepreneur can take in the criticism and adjust however they see fit, including not at all, and everyone else in the room was able to absorb the information too. True community involves a lot more than critical questions at tech events, but the example illustrates what I think is a trend.

I’ve noticed a real shift away from pseudocommunity in Hamilton over the last year. People are just getting to know one another better, gaining more confidence, and learning to effectively and honestly communicate with one another. Of course that involves chaos and negativity. But that’s really just growing pains. You can’t really place Hamilton or any other city into one of these four stages. There is no end point, and it it will never be perfect. And that’s OK.